Our shopping and other financial transactions are increasingly moving to the internet, as we seek to take advantage of the ease and convenience of doing business online. Unfortunately, fraudsters are aware of this and are always looking for new ways to exploit it.

One type of scam that has become popular lately is triangulation fraud, where criminals pose as legitimate eCommerce resellers, but source their products using stolen financial information.

In the following sections, we’ll explore this new type of fraud, why it’s so dangerous, and what can be done to combat it.

First, let’s dive a little deeper into the question of “what is triangulation fraud?”

What is Triangulation Fraud?

Triangulation fraud is a type of eCommerce scam where a fraudster poses as a legitimate seller on an online marketplace. When a buyer makes a purchase from them, the fraudster buys the requested product from another seller using stolen credit card data, and then ships it to the unsuspecting buyer.

How Does Triangulation Fraud Work?

A triangulation fraud scheme begins with a fraudster stealing credit card information, then setting up a storefront on a personal website or eCommerce marketplace (like eBay or Amazon). Next, the fraudster picks a legitimate online seller – often one with popular semi-luxury goods and automated checkout and delivery – to be a “supplier.” The fraudster then lists the wares of the “supplier” for sale on their own storefront, usually at below-average prices.

When a customer orders a product from the fraudster’s storefront, the criminal buys the product from the “supplier” using stolen credit card details and has it shipped to the customer’s address. The actual cardholder then likely files a chargeback against the “supplier,” who has to refund the victimized cardholder and can’t get back the sold item.

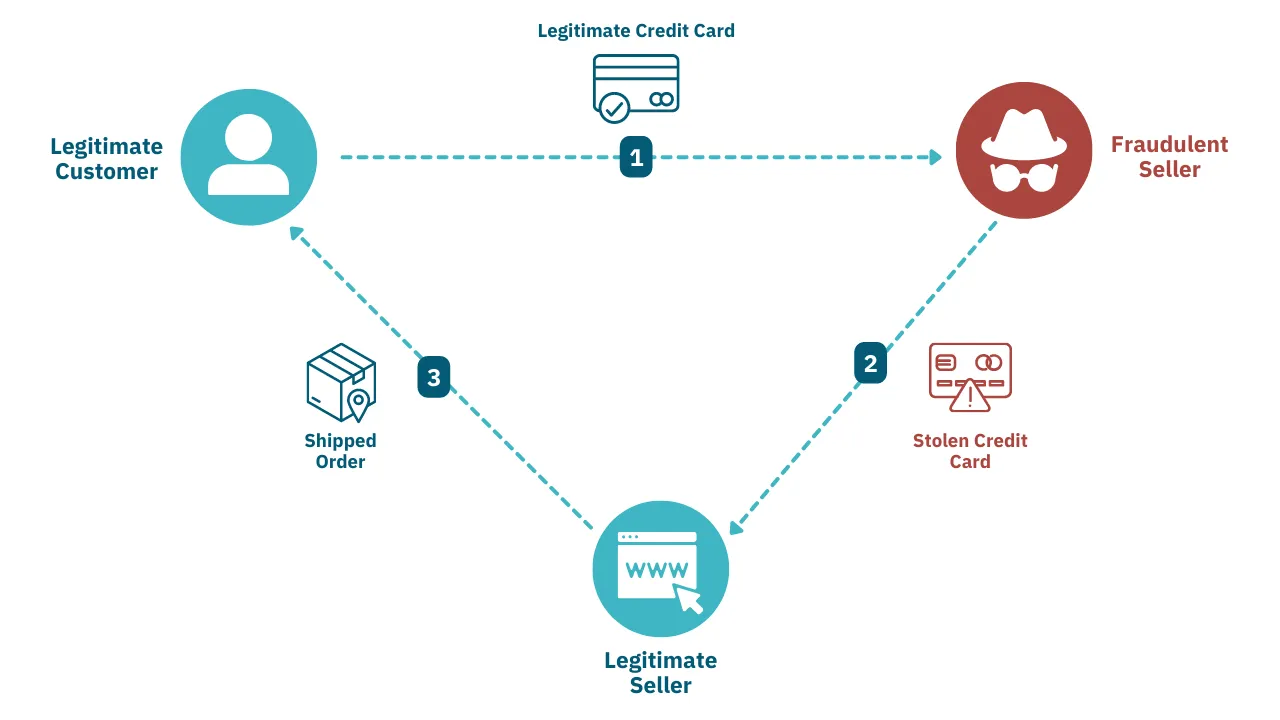

Triangulation fraud is so called because it involves three main parties:

- A fraudster: A criminal armed with stolen credit card information who poses as a legitimate seller on an online marketplace or other eCommerce storefront.

- A customer: A person with honest intentions looking to buy something online, usually at a discounted price.

- A supplier: An online merchant selling fairly valuable goods, especially one who sells at a high enough volume to need automated checkout and delivery services.

Here’s an illustration of how it works:

To further explain, we’ll also break the process down into its main steps here.

Step 1: A fraudster steals credit card information

There are many ways fraudsters can illegitimately acquire other people’s credit card details. These include mass data breaches, mobile phone hacks, or phishing scams.

Step 2: The fraudster sets up an online storefront

This could be on a personal website using a platform like Shopify, or it could be on an established eCommerce marketplace like eBay or Amazon. The fraudster may even advertise on social media.

Step 3: The fraudster targets a legitimate seller as a “supplier”

They will usually pick a store that sells popular goods that are not overly expensive, and sells at high enough volumes that they’ve automated their checkout and delivery processes. The fraudster’s goal is to limit oversight on their transactions, so nobody suspects they’re being made with stolen information until it’s too late.

Step 4: The fraudster lists products from the “supplier” for sale

Often, they will position themselves as a reseller and list products at “too good to be true” price points to fool customers into thinking they’re getting a good deal.

Step 5: A legitimate customer purchases the fraudster

A legitimate buyer purchases something from the fraudster’s store, thinking that they’ve found a bargain and not realizing they’re being used as a money mule.

Step 6: The fraudster buys and ships the item from the “supplier”

The fraudster uses stolen credit card details to place an order with the “supplier,” setting the shipping address to that of the customer.

The results of this scheme are as follows:

- The fraudster walks away with the customer’s money.

- The victimized cardholder is left to file a chargeback over an item they didn’t purchase.

- The “supplier” loses the purchased item AND has to refund the victimized cardholder.

The Impact of Triangulation Fraud Schemes

Triangulation fraud affects people whose stolen credit card information is used to buy from “suppliers.” They may simply lose their money because they aren’t always aware of their right to file chargebacks.

Merchants targeted as “suppliers” are hit harder still: they not only have virtually no way of getting their sold product back, but they also usually have to refund the victimized cardholder whose billing details were used fraudulently.

This type of fraud often happens to the same company over and over again, and those losses can add up. Some estimates peg international business losses from card not present (CNP) classes of fraud – including triangulation fraud – at $130 billion US between 2018 and 2023.

The combination of lost revenues, fees for legal negotiations, and supply chain disruptions caused by triangulation fraud often causes victimized businesses to raise their prices to compensate for the shortfalls.

This fuels inflation and can lead to the company losing customers who can no longer afford its products. So schemes like triangulation fraud end up hurting the whole economy in the long run.

How to Detect and Prevent Triangulation Fraud

Triangular fraud can be difficult to detect because it can be hard to tell if someone behind a set of credit card details is legitimate or a fraudster, in contrast to them paying with a physical card in person. However, there are still some techniques for detecting fraudulent transactions, including the following:

Watch commonly-targeted item categories

Triangulation fraudsters tend to stick to selling specific types of items – ones that are expensive enough to turn a decent profit, but not so expensive that individual transactions might come under increased scrutiny. Cosmetics are a good example, but even items such as coffee machine capsules can be popular. Tuning your anti-fraud software’s rules to have a lower tolerance for transactions featuring these kinds of items is one strategy that can work.

Look for certain behavioral patterns or oddities

Seller accounts used for triangulation fraud are often fairly new and don’t have many ratings or reviews, but have a suspiciously large inventory of items. They may also be named similarly or share similar credentials (like email address, payment method, or BIN) if a fraudster is running multiple operations at once.

Significant differences between an account’s billing and shipping information may also be a red flag for a fraudulent merchant. Finally, several transactions initiated from the same place(s) in a short period of time can often denote fraudsters trying to get the most value out of their scheme before they’re found out.

Ask suspicious accounts for additional verification

If a suspicious merchant lists contact information on their account, use it and see how (or even if) they respond. One example is to charge the merchant a few temporary verification fees and then ask them what those amounts are. If the account owner can’t or won’t provide the correct information, it could be a sign that they’re a fraudster.

Analyze past transactions for unusual trends

Look at historical transaction data to see if you can spot any of the trends in types of items sold, account details, and/or account activity that may be indicative of triangulation fraud. Though it can take quite a bit of time and work, adopting a “big picture” view like this can make it easier to determine what’s normal economic activity and what might be fraud.

Have the right tools in place

A good security and fraud prevention software suite – especially one incorporating machine learning – can help with all of the above processes. For example, it can check when and where an email address behind a business account was created.

Or it can match credit card data to a person’s other online purchases to check if what they’re interested in matches up with what they’re buying. Other examples include checking a buyer’s internet connection or hardware signatures for abnormalities (such as VPN use) or instituting velocity checks to require additional credentials from accounts trying to initiate multiple transactions in unusually rapid succession.

Learn more about Unit21

Unit21 is the leader in AI-powered fraud and AML, trusted by 200 customers across 90 countries, including Green Dot, Chime, and Sallie Mae. One unified platform brings detection, investigation, and decisioning together with intelligent automation, centralizing signals, eliminating busy work, and enabling faster responses to real risk.